His novels also exhibit an “uncanny sensitivity to the most disturbing currents of our age – often before they become perceptible” ( Cowart, “Lady” 39).

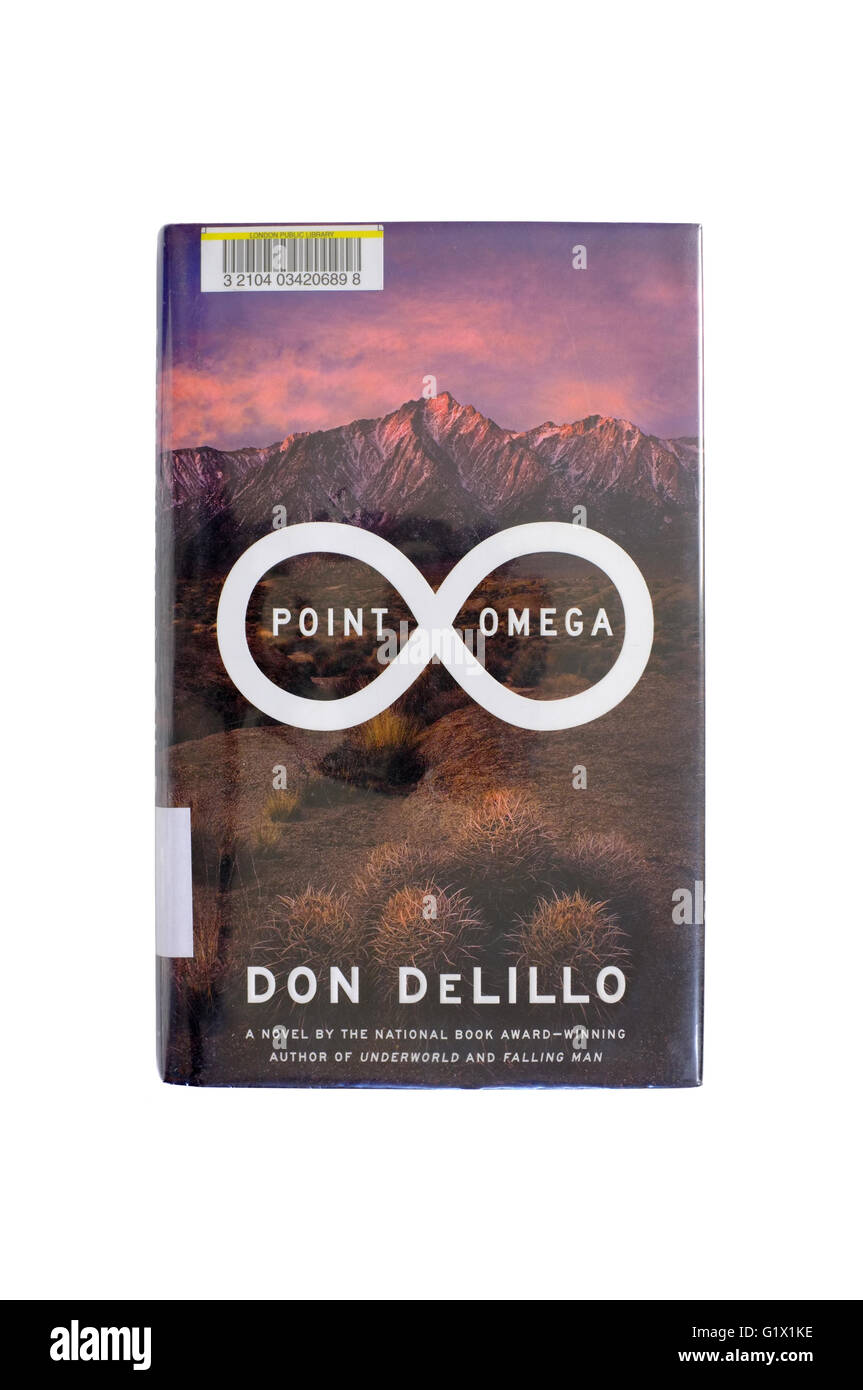

At the center of DeLillo’s aesthetic vision is the felt presence of death and its various manifestations: murder, suicide, terrorism, kidnapping, rape, totalitarianism, media simulation, paranoia, and consumerism, as well as a general despair and emptiness. But DeLillo’s anatomies of American culture more often than not take the form of autopsies. Time and again exhibiting a “prophetic tone” in his novels ( Wilcox 89), DeLillo “manage to be influenced by, in step with, and somehow one step ahead of the zeitgeist” ( Kavadlo 76). Such a reading reaffirms DeLillo’s faith in the power of fiction to cope with twenty-first century ills, and with death itself.ĭon DeLillo is regarded as “one of the key cultural anatomists” of contemporary America ( Wiese 2). To do so reads Point Omega as the story first and foremost of a character coming to terms with trauma and tragedy by turning to fiction, rather than by abandoning communication, as does Elster. This essay reads these bookending sections as also authored by Finley, rather than by an invisible narrator or an implied author. The chapters that bookend the novel tell, in an omniscient third-person mode, of an unnamed man viewing Douglas Gordon’s film 24-Hour Psycho at the Museum of Modern Art. The main narrative of the novel consists of his first-person account of a traumatic experience in the desert of California with Iraq War propagandist Richard Elster. It does so by reviewing the tripartite structure of the novel as being the product, in its entirety, of the protagonist Jim Finley. While criticism of the novel focuses on DeLillo’s recent metafictional gestures toward ineffability and existential despair, this essay reads the novel as a metafictional gesture toward the necessity of fiction in the twenty-first century. This essay proposes a method for re-reading Don DeLillo’s 2010 novel Point Omega.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)